Tru-Vue Home | History | Viewers | Filmstrips | Cards | Boxes | Cases | Special Sets | Sales & Advertising

The Visionaries of Tru-Vue: How a Bridge Company Paved the Way for a 3D Resurgence

Preface

In John Dennis’ 1980 article for Stereo World, he called Tru-Vue “stereo’s missing link” and expressed his excitement at discovering a 3D company that had actually flourished in the period after old-fashioned stereoscopes and before View-Master. “Missing link” captures it perfectly, and we felt that same excitement when we learned about Tru-Vue. A 1933 Tru-Vue Century of Progress viewer was the very first item in our collection, and Tru-Vue’s unique place in history has always fascinated us. Why were they able to be so successful through the Depression and World War II with their little filmstrip viewer?

So we dug a little further.

Turns out, the story of Tru-Vue is as much a business leadership story as it is a 3D technology story. Tru-Vue’s success is best understood in the context of the larger picture of early 1900s Rock Island, the history of the bridge & iron works company that gave rise to Tru-Vue, and the men who led both companies.

Tru-Vue wasn’t started by some Joe Blow dudes just kicking around on the streets of Rock Island, Illinois. It was incorporated and run by men who had already been executives of a major company — Rock Island Bridge & Iron Works — for almost two decades before Tru-Vue. One of Tru-Vue’s leaders had actually helped found Rock Island Bridge & Iron Works back in 1912. One had been an officer in 3 different companies. Another had served 2 terms as mayor, had served multiple stints in the military in different wars, and actually ran the Illinois public works department while working as an executive at Tru-Vue. Two of them served in leadership positions in an organization designed to increase business in Rock Island. So while the Tru-Vue leaders may not have had photography or 3D expertise, they were very well-connected, tenacious men, savvy in both business and politics.

True, they eventually succumbed and sold to a company with a better product: Sawyer’s. But in our opinion, after 20 years of worldwide success during difficult economic times, that’s not a failure. That’s a successful exit.

Here’s their story.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Early Years: A Bridge to the Future

Rock Island, Illinois, on the banks of the mighty Mississippi River, was a place of industrial promise in the early 20th century. The city, steeped in a rich history of bridge building, had witnessed the rise of monumental structures like the first railroad bridge across the river and the largest roller dam in the world. It was the perfect location for a new venture in the business of steel and iron—a venture that would eventually give birth to Tru-Vue.

The story begins on January 25, 1912, when Mark H. Kanary, the business manager of the Des Moines Bridge & Iron Company, made a bold decision. Believing that the shipping advantages of Rock Island would give his company an edge, he resigned from his position and set his sights on founding a new enterprise in the thriving industrial town. He brought his chief draughtsman along with him to the new company, Edward Manhard — a man who would go on to play a key role in Tru-Vue’s leadership.

“I believe the savings realized from the lower shipping costs will give my new company the upper hand over competitors on the west side of the river,” Kanary said, highlighting the strategic advantage of his new location.

On February 7, 1912, Kanary, alongside two business partners—Edward Manhard and Walter C. Murphy—incorporated Rock Island Bridge & Iron Works (RIBIW) with $30,000 in capital. The company’s mission was clear: to fabricate and erect structural steel, becoming a vital part of Rock Island’s industrial backbone. This business would last 58 years, with a dramatic spinoff in a completely unexpected direction that would influence a generation of 3D enthusiasts.

The Arrival of Walter A. Rosenfield: A Visionary Leader

In 1913, a dynamic figure emerged—Captain Walter A. Rosenfield. Rosenfield had made his mark in business, having taken over the leadership of Moline Wagon Company at the young age of 22 when his father, the company’s president, became too ill to continue running it. He eventually sold his stake in the Moline Wagon Company to Deere & Company and began looking for a new investment. Born and raised in Rock Island, Rosenfield had a deep connection to the town, and when he saw the potential of RIBIW, he didn’t hesitate to join.

“ I have always been a booster for Rock Island but I am more so than ever, as I am once and for all a fixture. You can’t get rid of me if you try … I am ready now for any old game that concerns Rock Island from peanuts and baseball to business and politics,” Rosenfield said, committing himself to both the city and the company.

Rosenfield’s entry into RIBIW marked a turning point. By 1914, just one year after joining, Rosenfield was named president of the company, succeeding Kanary, who stepped down after achieving early success. Under Rosenfield’s leadership, RIBIW quickly expanded, doubling its workforce and increasing its capital stock. The company was now preparing to become the largest bridge and structural steel plant west of Chicago.

But it wasn’t just RIBIW’s success that defined Rosenfield. In the same year, Rock Island was embroiled in political unrest and lawlessness. The notorious John Looney terrorized the city, and the crime wave led to martial law being declared in 1912. Rosenfield’s ambitious statement, “I am ready now for any old game that concerns Rock Island,” was about to be seriously tested.

Citadel of Sin

Rock Island was no sleepy little town by the river. It had its own mob-style underworld, complete with its own version of Al Capone. If you’re familiar with the movie Road to Perdition, you may remember Paul Newman’s character, the ruthless John Rooney. In real life, his name was John Looney, and during the years RIBIW was taking off, Looney was terrorizing Rock Island. The organized crime was so rampant with prostitution, blackmail, gunfights, and bombings that the city was dubbed the "Citadel of Sin."

In fact, in the same year RIBIW opened in 1912, the mayor of Rock Island, upset over a smear piece Looney’s “fake news” paper published about him, gave Looney a severe beating, with the police standing by watching. Rioting and murders ensued, and martial law was declared. The National Guard would remain in Rock Island for almost a month, and Looney eventually fled town.

When World War I began, many men from Rock Island left town to serve. Rosenfield, who had already been a captain in the National Guard, took time away from his duties at RIBIW to serve in the war and would eventually rise to the rank of major. With the town busy focusing on the war effort, Looney took the opportunity to slither back into town in 1917 and resume his criminal activities. His crime spree continued until 1922, when his son was murdered. Looney left town again to avoid his own conviction for a different murder.

Rosenfield played a key role in organizing a citizens’ committee in 1922 to combat the lawlessness and corruption that had terrorized the city. His vigorous efforts were a large factor in his successful race for mayor the following year. Rosenfield, already president of RIBIW since 1914, served as mayor of Rock Island for two terms, from 1923 to 1927. Six years later, Rock Island Bridge & Iron Works would begin producing Tru-Vue stereoscopes.

Rosenfield’s legacy was defined not just by his industrial success but also by his unwavering commitment to his community. His ability to juggle business, politics, and personal challenges would play a vital role in shaping Tru-Vue’s future.

The Birth of Tru-Vue: A Leap into Innovation

Fast forward to the early 1930s. The Great Depression was in full swing, but within RIBIW’s walls, a new opportunity was taking shape. Joshua H. Bennett, who had become affiliated with RIBIW in early 1933, was a passionate inventor who’d spent years working on the design of a stereoscopic viewer that used motion picture film instead of the traditional cardboard slides. His Tru-Vue viewer was initially created to showcase the progress of the Mississippi River Dam #15—a monumental engineering feat and a key project located near Rock Island.

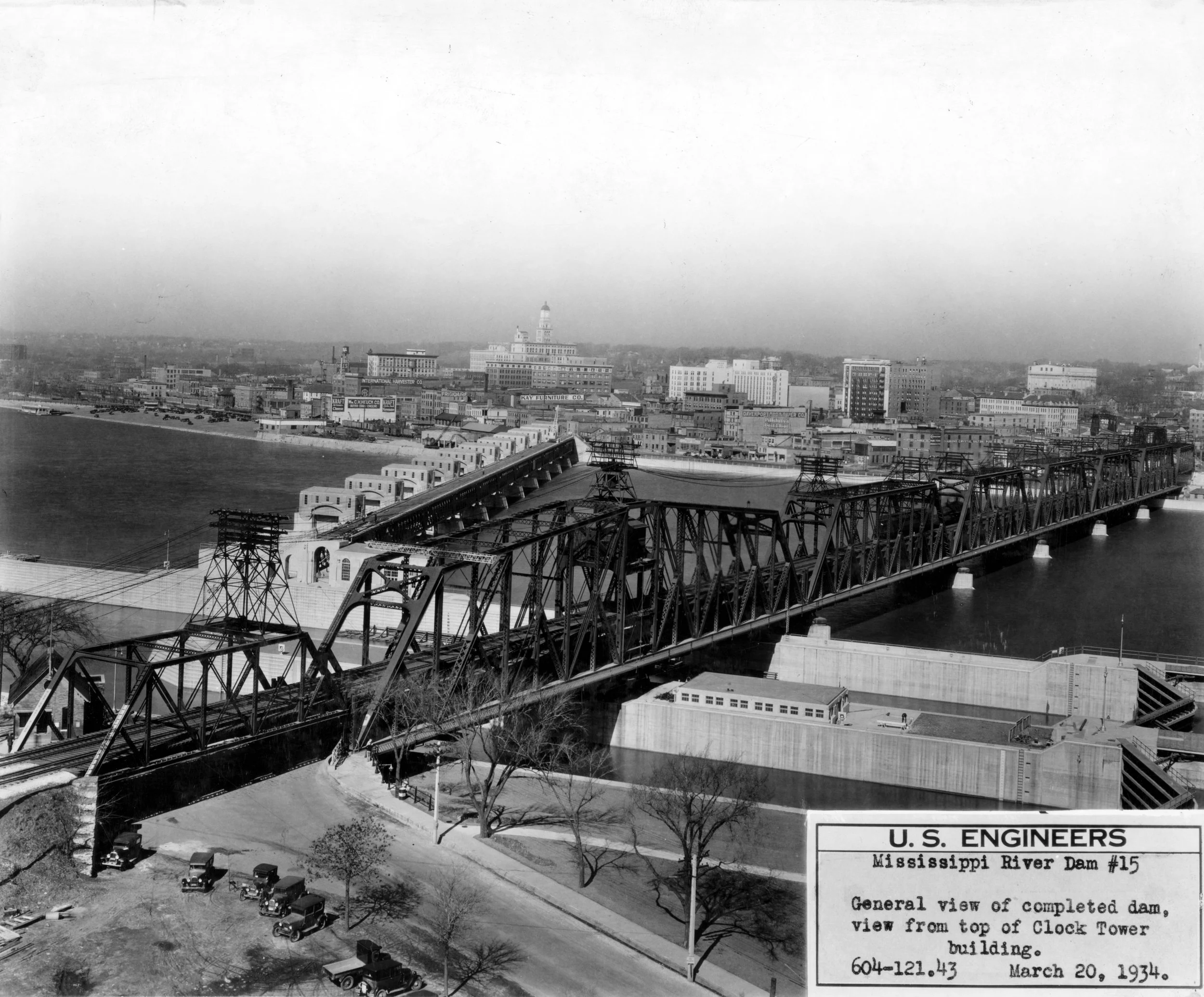

March 1934 View of Completed Dam #15. (Image available from the U.S. Library of Congress's Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID ppmsca.17351)

Lock and Dam No. 15, completed in 1934, was one of the pivotal structures on the Mississippi River designed to help improve navigation. The project was so significant that it became a focal point for one of RIBIW’s early Tru-Vue films. The company’s initial "Locks and Dam No. 15" film, showcasing the construction and operation of this critical infrastructure, was a great example of the educational potential the Tru-Vue offered.

Box for Tru-Vue's Dam No. 15 filmstrip

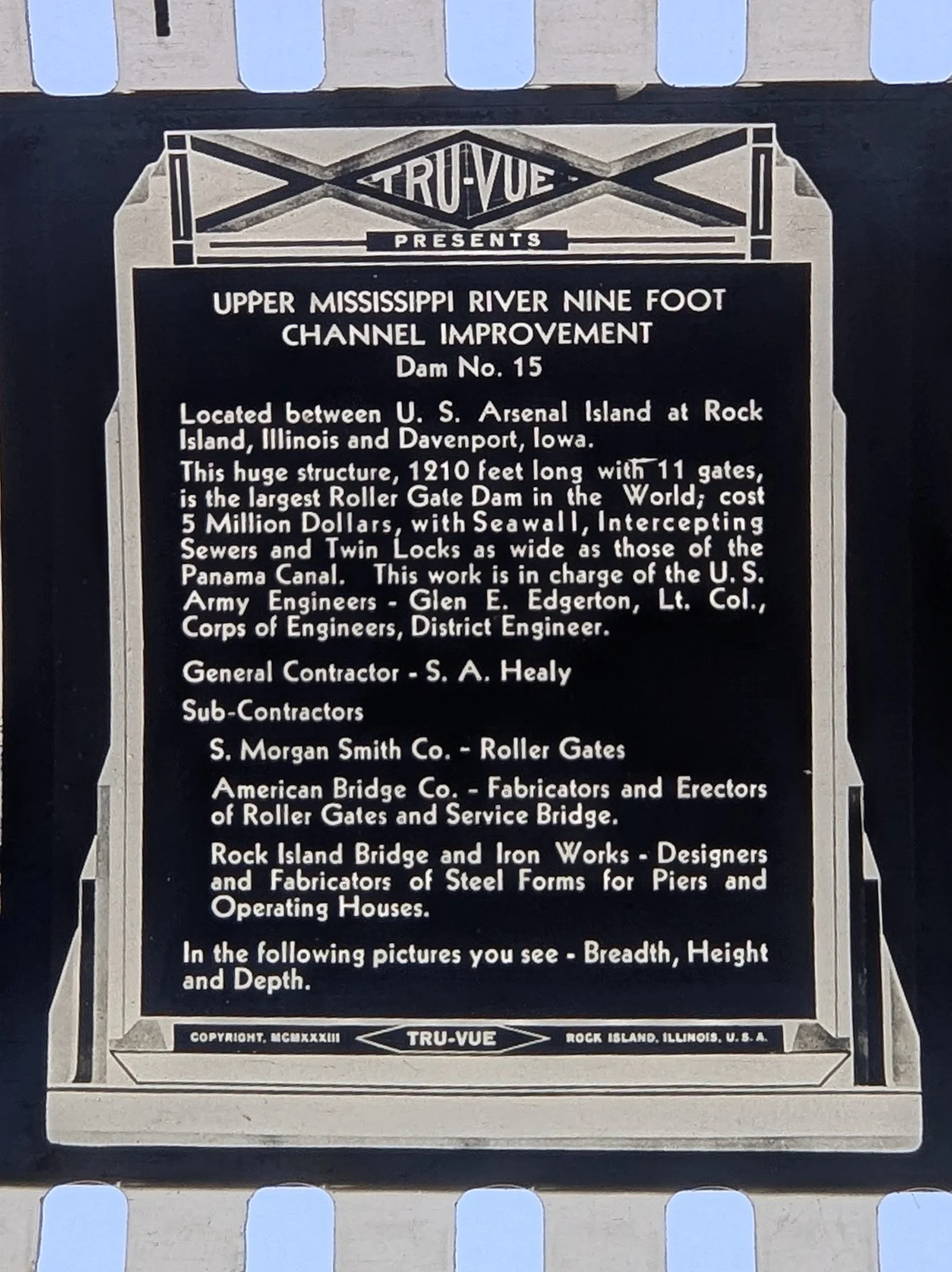

Title frame: Upper Mississippi River Nine Foot Channel Improvement - Dam No. 15

Filmstrip frame: Details of Cofferdam construction - each circular cell is a stable unit.

Filmstrip frame: Erecting service bridge, roller gate, and operating machinery

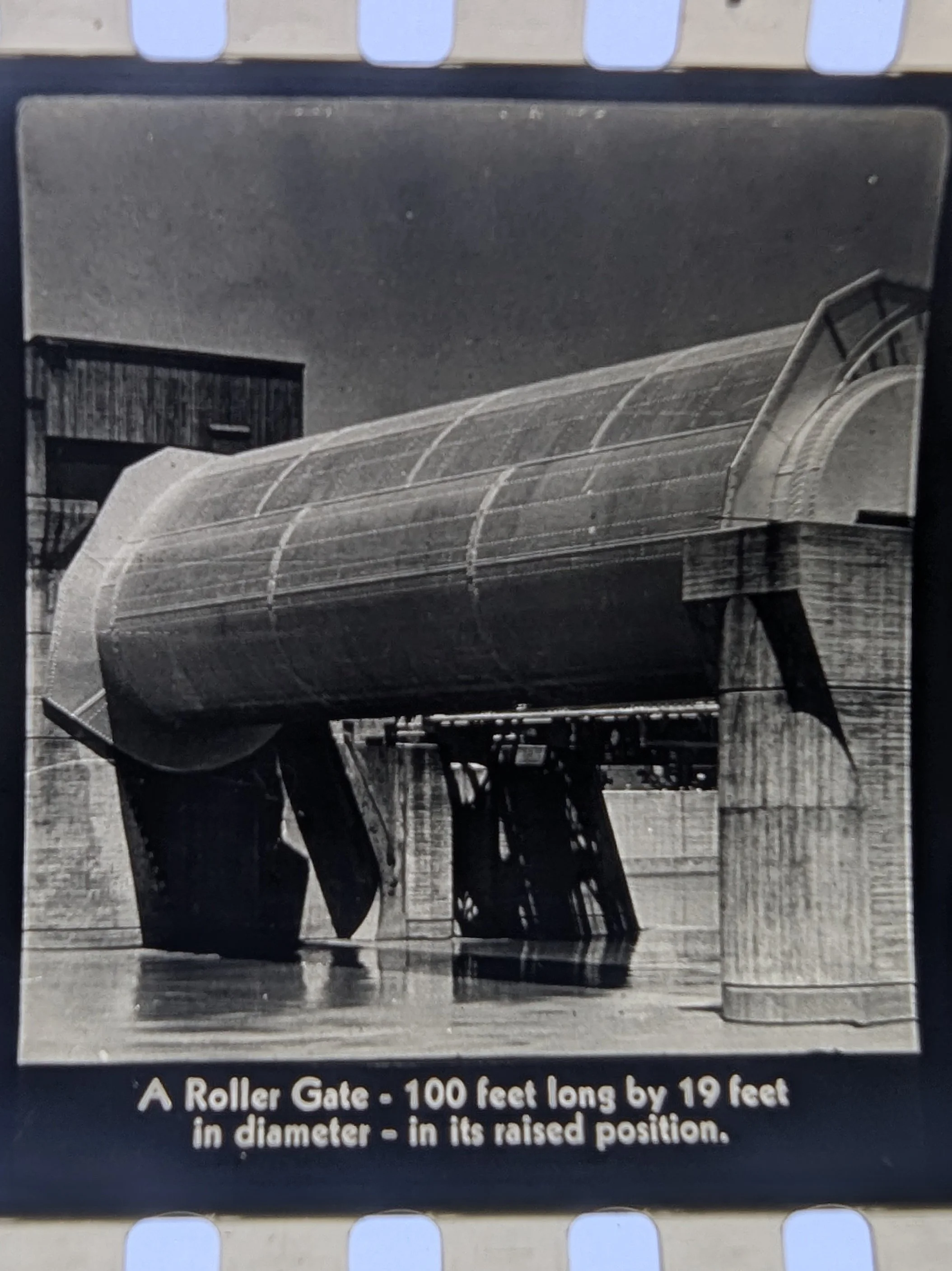

Filmstrip frame: A roller gate - 100 ft long x 19 ft in diameter - in its raised position

Filmstrip frame: Finished concrete walls of operating house on Pier No 1 - South elevation

Highlighting the dam project may well have been how Bennett became associated with RIBIW in the first place. Maybe Bennett approached RIBIW with the idea because of the manufacturing capabilities of RIBIW; maybe Rosenfield or someone else at RIBIW sought out Bennett, knowing of his work on the 3D filmstrip viewers. How Bennett’s association with RIBIW came to be is unclear. What we do know is that Bennett brought the viewer concepts with him when he got to RIBW. We also know that at least one Tru-Vue filmstrip existed before Bennett became affiliated with RIBIW. It was a 1931 filmstrip titled “Marvels of Plastic Photography” promoting the publicity applications of 3D, and was found in a cardboard viewer called Reel-Vue. Both the Reel-Vue viewer and this early Tru-Vue film were made in nearby Chicago. There is no reference to Rock Island on the film’s title or end frames, as is the case with other Tru-Vue films, and we have not found this film listed in any previously published Tru-Vue film lists. It’s entirely plausible that Bennett showed up at RIBIW’s door with something like this Reel-Vue & film as a demo.

1931 Tru-Vue film "Marvels of Plastic Photography." From our collection.

Viewer the early Tru-Vue film was found in. From our collection.

Bennett wasn’t the first or the only one to experiment with the use of 35mm filmstrips for 3D. Well over a decade earlier in France, Jules Richard had designed the Homéos stereoscopes to use 35mm filmstrips as 3D media. In the U.S., in 1928, Andre Barlatier filed a patent for the filmstrip stereo viewer that would debut in 1929 as the Hollywood Filmoscope. In addition, Herman A. De Vry of Chicago was working on the De Vry stereoscope, and the Novelart Manufacturing Co. in New York was working on a filmstrip-based stereoscope called Novelview.

While Bennett’s device was originally used to document and showcase RIBIW’s dam project, the wider market potential was not lost on Rosenfield. Always an opportunist, he recognized the potential of the Tru-Vue beyond its industrial uses. The Century of Progress World’s Fair would be opening in Chicago on May 27th, and he wanted to be there with Tru-Vue.

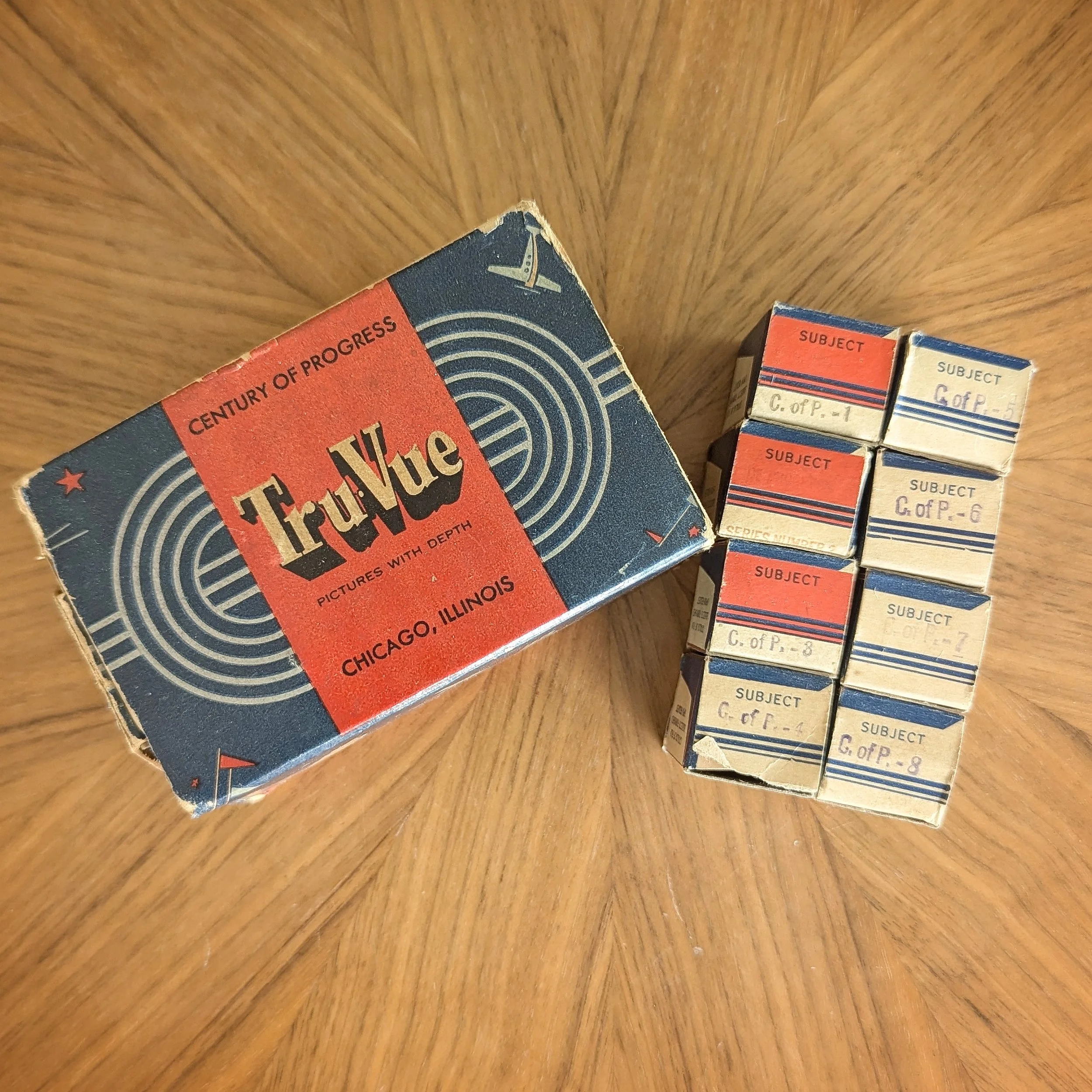

Eleven models of the Tru-Vue viewer were designed before finalizing the stereoscope casing that Bennett would file a design patent for in June of 1933. Herman De Vry filed his patent for the De Vry viewer in July 1933, just one month later. Bennett’s design patent (US-D090564-S) was granted in August 1933, and De Vry’s stereoscope patent (US-2003480-A) was granted in June 1935. And while De Vry also created a few films of the Century of Progress World’s Fair (six that we know of), Tru-Vue went the extra mile with their coverage and marketing. They created special Century of Progress-themed viewers that came in colorful, fun World’s Fair-themed mailer boxes. Tru-Vue’s photographers shot numerous photos covering the fair, including one of its main attractions: Sally Rand. They produced 4 Century of Progress films and 2 Sally Rand films, which they marketed to the public as early as September 1933.

Tru-Vue viewer with 1933 World's Fair logo

World's Fair-themed viewer box and 8 Century of Progress films (the last 4 produced later with the 1934 continuation of the fair.)

In October 1933, RIBIW officially announced the mass production of Tru-Vue, and sales began to soar. At that time, the bakelite & metal Tru-Vue devices were being made at the RIBIW plant located at 1601-03 Mill St, as were the films.

“We are manufacturing the Tru-Vue viewer and the films at our Rock Island plant,” stated Edward Manhard, who had become an integral part of the leadership team. “Orders have been pouring in, and we’re already looking beyond the current stock of World’s Fair, travel, and fairy tale films to create specialty films like ‘Locks and Dam No. 15.’”

By the end of 1933, the company went from producing 300 Tru-Vue stereoscopes a month to 50,000 per month, with orders coming in from all corners of the country. That kind of demand required 30 men working 6 days a week, 50 salesmen selling nationwide, and new digs: they moved the Tru-Vue manufacturing operation from RIBIW’s main plant on Mill Street to a larger space on the 2nd floor of the Nu-Way building at 3416 Fourth Avenue.

Tru-Vue had evolved into a groundbreaking product.

The Golden Age of Tru-Vue: From Local Success to Global Recognition

The success of Tru-Vue was swift and unmistakable. By 1934, the company had expanded into a global operation, with new branches in New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, and London. What had begun as a local novelty quickly became a sensation worldwide.

The Century of Progress World’s Fair opened for a second run in 1934, and Tru-Vue once again offered a custom viewer, this time with the 1934 faceplate (a rare find today.) They produced 4 additional films of the Fair, bringing their total of Century of Progress films to 8. They published want-ads that beckoned to experienced salesmen, promising a product with “proven acceptance” and a “World’s Fair tie-in.” Custom viewers were also made for the Fred Harvey restaurant chain, followed by special gift-boxed sets to sell at the restaurant’s locations, and special sets featuring golfer Bobby Jones. Tru-Vue’s influence extended far beyond entertainment and education, with industrial and promotional films becoming a key market for the stereoscope. Companies used the Tru-Vue to showcase their products in ways never before possible, further driving the demand for the device. In 1933, Alice Hughes wrote a piece about Tru-Vue for The New York American newspaper. She lightheartedly bemoaned the fact that the device was introduced first in Chicago, because of the World’s Fair, rather than in New York as would ordinarily be the case for new products. She enthusiastically declared:

“Take our word for it, it won’t be long before salesmen, instead of letting loose a flow of oratory, will whip a Tru-Vue out from their pockets and in two minutes the customer will grasp clearly and in three dimensions what it would need half an hour to explain.”

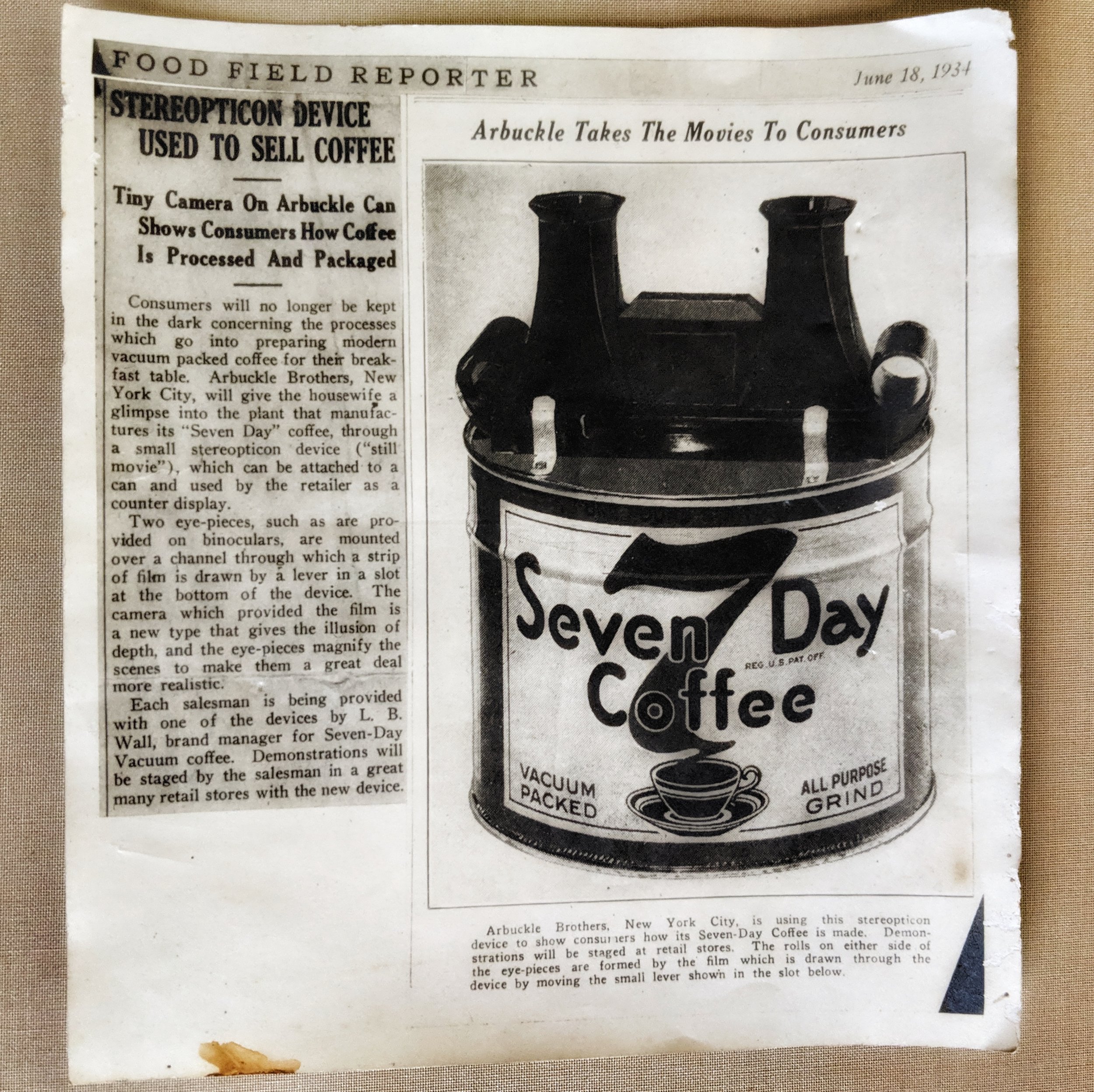

This copy of a 1934 article reporting on Arbuckle’s use of Tru-Vue to showcase its product, was found in a Tru-Vue salesman’s briefcase in our collection.

In 1934, as the demand continued to surge, Joshua H. Bennett, the inventor of the Tru-Vue viewer, moved into a new role as general sales manager for the eastern division. The company leased the 18th floor of the RKO building in Rockefeller Center to house the eastern offices. The demand for the Tru-Vue was so high that by the end of 1934, the company was manufacturing and shipping Tru-Vue devices in the tens of thousands each month. The Illinois Dental Journal reported that Tru-Vues were being given to patients sitting in dental chairs to reduce nervousness and take their minds off the dental work. Arbuckle Brothers, using the Tru-Vue advertising campaign shown in the image above, landed a long-sought-after account. Proctor & Schwartz Electric Company successfully used Tru-Vue in a 3-day promotion of their Snap-Speed electric iron — one of the largest advertising campaigns for an iron, at that time.

Between 1935 and 1937, RIBIW had been seeking to reorganize financially and incorporate Tru-Vue. One obstacle was Bennett, the patent owner, and his claims for royalties. After two years of negotiations, Bennett finally settled for $3,220 and assigned RIBIW the title to the Tru-Vue patent. Tru-Vue was incorporated on February 17, 1937, with Walter A. Rosenfield as president, Edward Manhard as vice president, and Maurice Carlson as secretary-treasurer & manager — all of them RIBIW executives. Years earlier, both Carlson and Rosenfield had been leaders of the Rock Island Club, an organization dedicated to encouraging and promoting the manufacturing and mercantile development of Rock Island. Given that bit of context, we see that it’s less about the oddity of a bridge company making 3D viewers and more about the mindset and history of the men leading that bridge company — men who had long been passionate about finding ways to put Rock Island on the business map.

The company issued 3,000 shares at $10 each, officially separating from RIBIW and establishing itself as Tru-Vue, Inc.

Tru-Vue’s Leadership Team

By the end of 1937, Tru-Vue was firmly established as a household name. The company’s business, which had once been seasonal, had shifted to year-round demand. While Christmas remained a busy season, summer saw the heaviest shipments due to the surge in tourism to national parks, where Tru-Vue viewers were in high demand. The company’s leadership began to build up an export business, claiming Tru-Vue was now known all over the world. The company further claimed that 1937 saw a 100% increase in sales over the previous year, with fifty new films added to the growing library.

Tru-Vue building at 121 Fourth Avenue in Rock Island, Illinois. (Photo from the Tru-Vue Factory Tour film in our collection)

Just ahead of the opening of the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco on February 18, 1939, Rosenfield and Carlson were in San Francisco negotiating arrangements to photograph the Golden Gate Exposition. They also had plans to photograph the New York World’s Fair, which would be opening on April 30, 1939. They hoped both fairs would result in a large amount of business. They predicted correctly, reporting substantial gains in their year-end report.

Also at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, Sawyer’s, who would turn out to be Tru-Vue’s strongest competitor, debuted their 3D viewer: the View-Master.

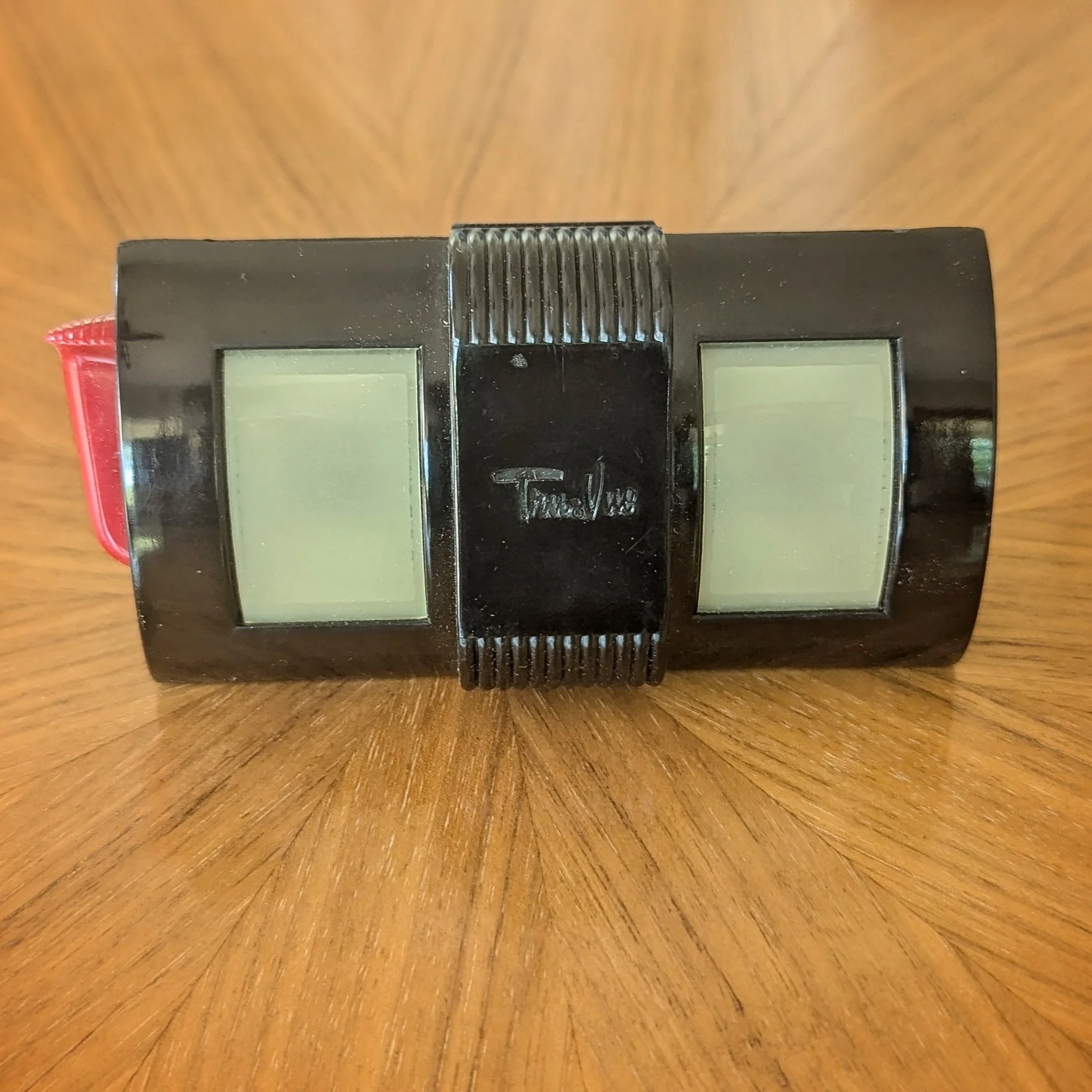

Tru-Vue had outsold and outlasted the other big 3D filmstrip viewers of its day: Filmoscope, De Vry, and Novelview. But the competition from Sawyer’s View-Master, with its easy-to-use reel format and vivid color pictures, was stiff. For a few years, Tru-Vue had been working on a new streamlined version of the Tru-Vue viewer. It was developed and patented by Gifford M. Mast (US-2326718-A) and had ⅓ fewer parts than the previous Art Deco-style viewer. In 1940, they finally released it, along with new films of Florida and California, motion picture stars, and cartoons — bringing their library total to over 300 subjects. Yet, despite claiming that they’d shipped over 100,000 viewers and “enough film to reach from the Tri-Cities to St.Louis” and that their viewers were now being sold at almost every large department store in the country, in the end, Carlson had to report that 1940 had only been average for Tru-Vue. Satisfactory, but average.

Ad for the new streamlined Tru-Vue, printed on a Tru-Vue envelope in our collection.

All black streamlined Tru-Vue, from our collection

World War II: Adapting to the Times

In 1941, Rosenfield was appointed by Governor Dwight H. Green to direct the Illinois Public Works. He resigned as treasurer of RIBIW (a role he’d held since its founding in 1913!) but stayed on at Tru-Vue, since he didn’t see any conflict of interest between public works and stereoscopes.

With the onset of World War II, Tru-Vue faced challenges, but it also found new opportunities. Unlike its competitors, Tru-Vue used black-and-white film, which was not subject to the wartime restrictions placed on color film. Additionally, in November 1944, the War Production Board gave a spot authorization to Tru-Vue to continue to produce civilian goods, specifically their “stereoscopic viewing device.” This allowed the company to continue production while others faltered. Tru-Vue even received contracts from the American Red Cross (10,000 viewers and 60,000 different films) to provide to soldiers in their Rest and Rehabilitation Centers around the world, and from the USO to provide entertainment and education to soldiers in their 500 camps. However, shortages of printer’s ink did impact Tru-Vue, resulting in films temporarily being sold in plain white boxes that can still be found today.

Special set for the American Red Cross, from our collection

Viewers and film inside the American Red Cross set

The Decline and Legacy

Employees assembling Tru-Vue viewers. (Photo from the Tru-Vue Factory Tour film in our collection)

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Tru-Vue faced increasing competition from View-Master, which was becoming a staple in homes across America. Briefly, Tru-Vue’s incorporation was dissolved in January 1947 — reverting to a division of RIBIW once again — and then incorporated again as a separate entity in 1948. It’s unclear why this happened — perhaps to take financial advantage of new laws, straighten out stock ownership, or maybe to prep for a future sale. In any case, Tru-Vue made several changes to try to stay competitive against View-Master. They began producing color filmstrips called “Stereochromes,” a pursuit that had been delayed by the war. They created films featuring the Disney cartoon characters for which they owned the 3D rights. They shortened their filmstrip length, first by putting 2 pictures in one frame, and then, when that didn’t sit well with the public, reducing the number of frames from 14 to 10. And they more aggressively pursued markets like television and industry. In October 1949, Fred B. Ingram, Tru-Vue’s chief sales representative, spoke of their expansion into the television field and commercial areas:

“We have just finished a film sequence on ‘Howdy Doody’ the hottest TV show in NYC and the east coast. Shortly we are going to shoot ‘Alice in Wonderland’ from drawings, and later supplement this with other familiar fantasies that we don’t have on hand yet. Tru-Vue has also introduced the viewer to industry. Now products manufactured by various industries can be seen through our viewer.”

Color Tru-Vue film set featuring Disney characters, from our collection.

Color Tru-Vue film set for commercial use, featuring Fruehauf, from our collection.

Ingram maintained that their international business was doing well, pointing out that a large consignment of stereoscopes had recently been shipped to New Delhi, India. Interestingly, he also mentioned that “England is out at the moment because of the pound devaluation” and stated that London had previously been a big foreign market for them. That statement is interesting because the following year, an almost identical “England” version of Tru-Vue appeared called “True-View,” produced by the Signalling Equipment, Ltd. (S.E.L.). Although the product spelling was slightly different and the set of films was entirely different, pretty much everything else about the English True-View viewer was the same as the American Tru-Vue: the logo, the box design, the viewer design, and the cocoa brown & ivory viewer colors being used for Tru-Vue at the time. Likely, the appearance of the English True-View right after American Tru-Vue lost the England market is not coincidental. What’s not clear is whether Tru-Vue licensed this arrangement or sold its equipment to S.E.L. Either way, knowing Rosenfield’s business sense, surely Tru-Vue profited in some way.

The nearly identical American Tru-Vue and English True-View. From our collection.

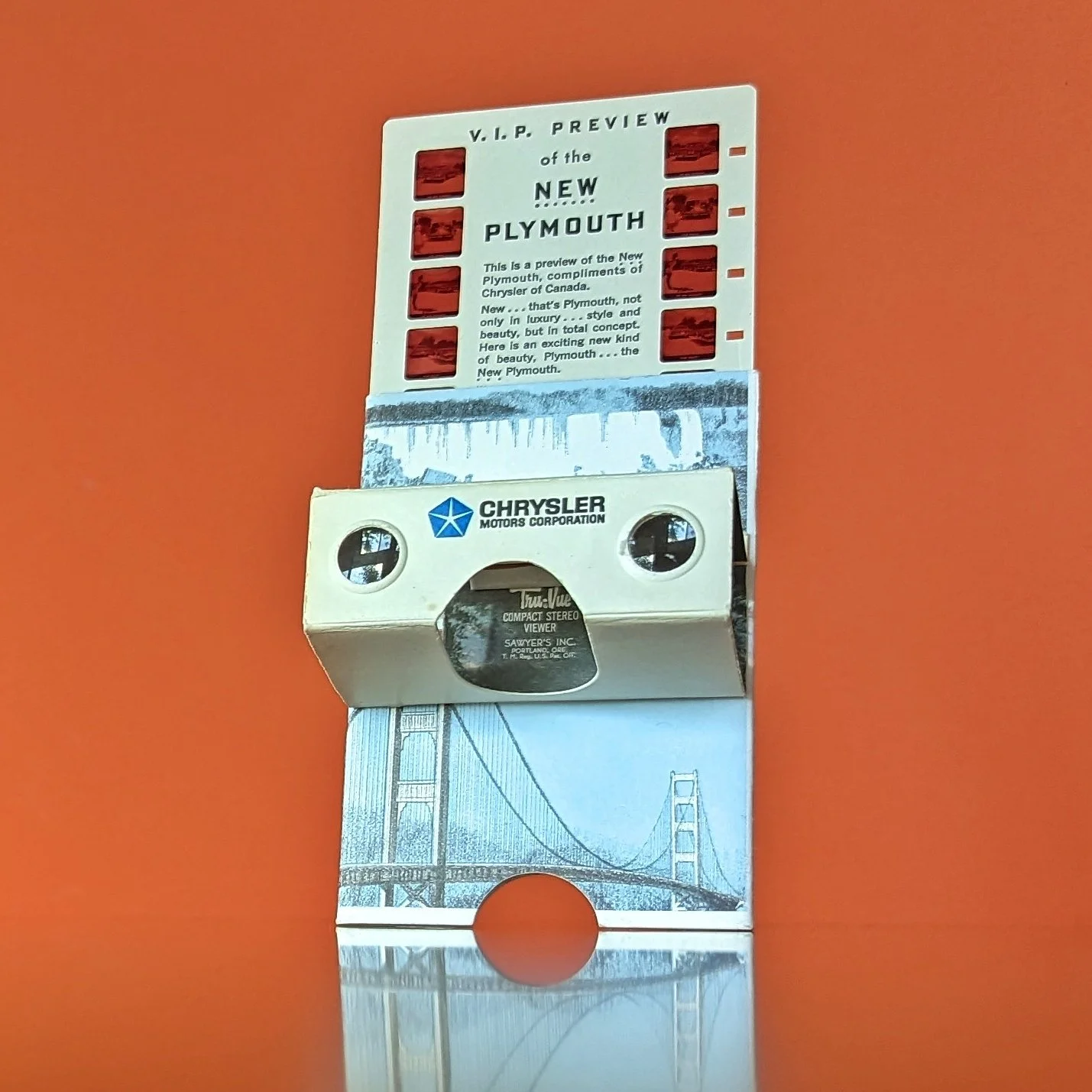

Unfortunately, none of the changes were enough to keep Tru-Vue and its filmstrip format competitive. Sawyer’s had been interested in acquiring the Disney cartoon character rights that Tru-Vue owned, and in early 1951, Harold J. Graves (president of Sawyer’s) and his staff were in Rock Island for two weeks inspecting the Tru-Vue plant and books in consideration of a purchase. The deal was made, and Rosenfield retired. Sawyer’s took a temporary lease on the property in Rock Island, and then relocated Tru-Vue to Beaverton, Oregon. Filmstrips continued to be made for a very short time before the format was abandoned entirely. After that, filmstrips were sold until the stock was gone. Sawyer’s changed Tru-Vue to a multi-pair card format and developed a line of plastic 3D viewers marketed exclusively for children. They also continued to market Tru-Vue to companies, pushing their new card format as a promotional tool, paired with either their smallest “Junior” plastic viewer or their folding cardboard viewer. Chrysler of Canada would go on to use their new card format for almost a decade in the 1960s.

First viewer in the new Sawyer's Tru-Vue product line, designed for multi-pair cards.

Sawyer's 2nd Tru-Vue viewer, the Deluxe, lighted viewer

Sawyer's 3rd Tru-Vue viewer - the "Junior" - was used to promote Chrysler of Canada for almost a decade. From our collection.

Sawyer's cardboard Tru-Vue Foldpak viewer promoted as a sales aid. From our collection.

Sawyer's Tru-Vue cardboard viewer branded for Chrysler of Canada. From our collection.

The 1951 Sawyer’s purchase marked the end of an era for Tru-Vue as an independent entity. Maurice Carlson passed away 2 years later in December 1953 at age 66. Walter Rosenfield passed away at the age of 82 in 1959, eight years after the sale of Tru-Vue to Sawyer’s and one year after RIBIW was sold to Macomber, Inc., which would eventually close the steel plant in 1970. Edward Manhard passed away in 1961 at age 79. In the nearly 20-year run of Tru-Vue, all 3 men had served in the highest executive levels of Tru-Vue, going back and forth between President, Vice-President, Secretary, and General Manager roles. At the same time, all 3 men served on the highest executive levels of Rock Island Bridge & Iron Works from its earliest years, with Manhard being on RIBIW’s original founding team.

There’s no doubt that Rosenfield, Carlson, Manhard, and the rest of the Tru-Vue players under their leadership (Joshua Bennett, marketing team, factory workers, engineers, photographers, artists, and salesmen) had changed the landscape of visual technology. Through their vision, business savvy, and perseverance, they ushered in a more modern and affordable era of 3D viewing that reignited mass interest in seeing the world with depth and dimension.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sources

Magazines

Illinois Dental Journal, April 1934

Newspapers

Advertising Age

March 30, 1935

Des Moines Tribune

January 26, 1912

The Daily Times, Davenport, IA

February 7, 1912

November 5, 1936

October 26, 1949

February 6, 1951

The Rock Island Argus

December 20, 1911

June 24, 1913

June 17, 1914

October 2, 1933

November 24, 1933

December 30, 1933

December 30, 1933

February 18, 1937

December 31, 1937

December 31, 1939

December 31, 1940

January 17, 1941

December 21, 1943

January 11, 1947

September 3, 1948

December 8, 1953

January 20, 1961

January 7, 1970

The Roosevelt Standard, Roosevelt, Utah

April 20, 1927

The Dispatch, Moline, IL

November 3, 1933

November 20, 1944

November 27, 1946

Chicago Tribune

December 30, 1933

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle

February 23, 1934

Mt. Vernon Register-News, IL

July 29, 1959

Books

Stereo Views - An Illustrated History & Price Guide, 2nd Edition, John Waldsmith

Webpages

“Stereo’s Missing Link,” John Dennis

“Tru-Vue,” Tom Martin

Continue to explore our Tru-Vue collection:

Tru-Vue Home | History | Viewers | Filmstrips | Cards | Boxes | Cases | Special Sets | Sales & Advertising